Hydrogen is a potential carbon neutral source of energy.

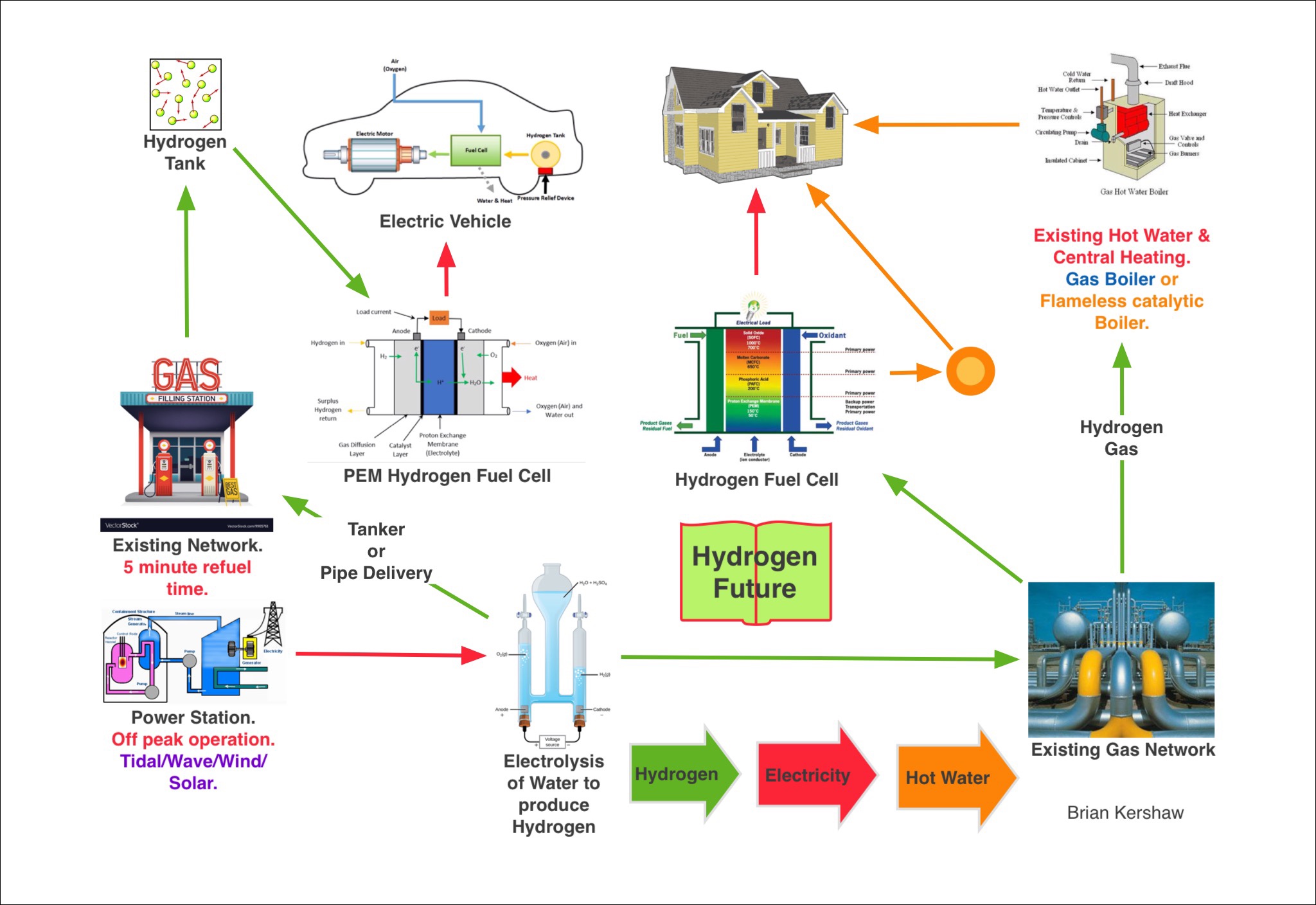

Hydrogen can be used as a fuel by burning it directly as a gas, thus replacing North Sea Gas in existing gas boilers using the existing infrastructure. Some concerns have been expressed about how a gas such as hydrogen with a very small molecular size could more easily leak from the existing network pipelines. This would have to be tested prior to any roll out and a solution found. However, rural properties currently using kerosine boilers or LPG could be easily converted to hydrogen and a gas storage tank substituted for the existing oil/LPG tank. The only emissions from the boiler would be water vapour thus it is a zero carbon solution.

Similarly hydrogen could be used in a conventional internal combustion engine as fuel for cars which could be filled up at a filling station in the normal way. The alternative approach would be to convert the hydrogen into electricity via an onboard fuel cell and then use this to power an electric motor. Again you would refuel at a conventional filling station, taking less than 5 minutes for a range of 500miles, and water would be the only emission. The second method is the most attractive in terms of smooth quiet gearless transmission of power and superior acceleration for a given engine size. It would be a relatively simple and quick process to convert a petrol pump to an hydrogen pump and the infrastructure could be provided relatively quickly.

The major concern is that hydrogen is explosive and crash proof containment and automatic fuel cut off systems would be essential. This is not that difficult to achieve, and after all petrol is highly inflamable and that hasn’t put us off in the past. In fact hydrogen is safer than petrol, being the lightest element in the universe, if it leaks at all it vents vertically upward at speed. Therefore, even if it were on fire it would be a narrow upward burning jet, unlike petrol which spreads out over a wide area spreading the fire along with it.

Safety issues aside, it would be quite easy to manufacture hydrogen at home from your domestic electricity supply. To produce a truly zero carbon emission system the electricity generating board would have to generate electricity centrally from tidal barrages, wave power, hydro, wind, photovoltaic etc. Surely this would be so easy to achieve with our five thousand miles of coastline and the highest winds speeds in Europe, and the fact it relies on already proven technology. The cost would be small compared with other zero carbon solutions such as nuclear power.

Electrolysis Cells adjacent to the power station could mass produce hydrogen from water, the water being recoverable in potable form from the individual fuel cells. Oxygen would also be produced from this process which could be used for other purposes, thus bringing down the manufacturing costs. In fact if the oxygen byproduct were to be vented into the atmosphere it would replace the oxygen used from the atmosphere by the fuel cells in the cars. Thus the transport network would be oxygen neutral as well as carbon neutral.

It must be emphasised that the use of hydrogen fuel cells is the most appropriate and practical solution to a greener transportation system, not the current roll out of Lithium ion cell powered vehicles. All the major car manufacturers are developing hydrogen fuel cell technology but can’t roll it out yet due to lack of refuelling points.

Lithium Ion is not the way to go for so many environmental and other reasons. For example consider pulling into a medium size service station, with a throughput of some 100 cars per hour. Over that one hour that you are plugged in, being charged with a 100 mile range of energy, 100 conventional petrol vehicles would have passed through. Therefore to achieve the same average throughput of electric vehicles you would require 100 charging points and an enormous forecourt to accommodate it. A normal fast charge port is rated at 50kw. That’s 5000kW (ie 5 Meggawatts) per medium size service station. To put this in perspective, this is twice the output of a typical onshore windmill when it’s windy enough to operate. On top of this is the inconvenience of having to break your journey by at least an hour every 100 journey miles. At teatime when everyone arrives home from work and plugs in their battery the electricity grid would probably shut down. The home chargers are much smaller typically 7kW and would take 4-6 hours to put 100 miles of charge back in. In a worst case scenario if the 40 million licences vehicles on British roads were plugged into the grid at teatime that would place an additional load of 280 GW onto the national grid at a time when demand is very high anyway. To put this in perspective the current total output of the national grid is a mere 100 GW. Further, unless you have a private driveway attached to your property you would have to have a personal charging point installed on the pavement outside your home.

The present generation of lithium Ion batteries are unlikely to last the life of the vehicle and will need replacing at enormous cost. The range advertised for Lithium battery powered vehicles is possible over optimistic. For example would you risk running your battery down to zero charge. In any case the service life of a lithium battery is considerably extended by restricting the state of charge to stay within the range 30 to 70% of full charge. Lithium is already in short supply and plans are going ahead to dredge the virgin ocean floor to supply the ever growing demand. The system only works, charging time and range accepted, at the moment because only the rich can afford one. Unless a completely different type of battery is invented that addresses all these issues, hydrogen fuel cells are the only practical way forward.